Does machine learning justify changing our need for a glass box?

Take a look at this paper. It’s titled, “Deep learning and the Schrödinger equation”. It’s implications are really interesting; first let’s take a look at the paper’s claim.

“We have trained a deep (convolutional) neural network to predict the ground-state energy of an electron in four classes of confining two-dimensional electrostatic potentials. On randomly generated potentials, for which there is no analytic form for either the potential or the ground-state energy, the neural network model was able to predict the ground-state energy to within chemical accuracy, with a median absolute error of 1.49 mHa. We also investigate the performance of the model in predicting other quantities such as the kinetic energy and the first excited-state energy of random potentials. While we demonstrated this approach on a simple, tractable problem, the transferability and excellent performance of the resulting model suggests further applications of deep neural networks to problems of electronic structure.”

So what does this mean in laymen’s terms? It basically means that we can give a computer a lot of different examples of any given problem we want it to solve and can get answers for questions about that problem that are really accurate.

Let’s say you were looking at some physical phenomenon you wanted to understand. (Let’s use something like the probability of finding a tennis ball that you dropped in a hole in the ground.)

Now in general if you drop a tennis ball in a big hole in the ground it usually falls towards the center where the hole is the deepest. So it’s unlikely that it will get caught on the outer fringes, but still possible.

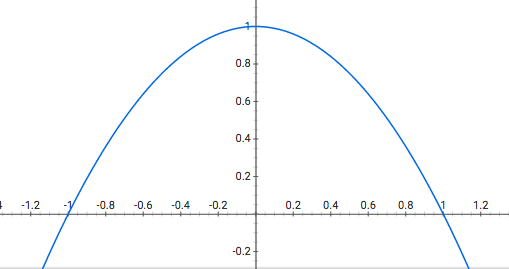

So you might get some sort of curve of changing probability that looks like this, where x=0 is the center of the hole and the further out you go, the lower the probability gets.

ratchet probability example of how likely you are to find a tennis ball.

Now imagine instead of a tennis ball, you’re looking at an electron, and instead of gravity acting on the tennis ball, it’s now electric potentials that create coulomb forces on that electron that force it into a certain position.

This situation I’ve just described is called the quantum well; something you’ll see a lot in an introductory quantum mechanics course. The usefulness of the quantum well example is that you usually earn how to model it using the Schrödinger equation.

$$ i\hbar {\frac {\partial }{\partial t}}\Psi (\mathbf {r} ,t)=\left[{\frac {-\hbar ^{2}}{2\mu }}\nabla ^{2}+V(\mathbf {r} ,t)\right]\Psi (\mathbf {r} ,t) $$

You can read more about the Schrödinger equation here, but for our purposes what you should know is that it gets very complicated very quickly. The second you start trying to use it to model two tennis balls, things become very very difficult to solve, especially because we only have the probabilities!

The glass box

When we manipulate equations that we believe accurately model the real world, every valid manipulation of that model is something that we also believe to be “true”, and we continue to manipulate this equation until we arrive at a statement of interest to the question we’re asking. These models are sometimes called a “glass box”. This is because the process we are inspecting is one that we believe that we understand because the model we’re using works for that particular problem.

In the context of this paper something called a Convolutional Neural Network is used. It works by looking at thousands of input-output examples of the thing you want to model, and creates an approximation of the raw numerical operations that are applied to your input in order to “fake” knowing whatever the function actually is. This process of creating a numerical model that doesn’t have to know anything about the function it’s approximating is called a “black box”. We know what we put into the box and we know what comes out, and that’s it. Because we don’t really know what the model looks like other than the numbers, we usually just test it to see how accurate it is and then use it for problems where we don’t have a glass box yet.

This concept of neural networks was actually invented in the 1950’s, but it’s only recently that this method of machine learning has exploded in popularity for solving complex problems. This paper is interesting because it enables us to use computers as black boxes to solve problems that were once thought to only be solved with glass boxes. Now we don’t need to understand a problem in order to be able to use an approximation of the answer. And before you say it, this has nothing to do with the hidden variables theory, which isn’t what we’re talking about. (That’s a question that Einstein)

Which models are better?

Well just looking at it heuristically we get exact accuracy with glass boxes but they can take a long time to develop and accurately research.

On the other hand we can get black boxes that can give us a 0.1% margin of error and provide us with models for a lot of different problems a LOT faster because all we have to do is collect some data and then train a machine learning algorithm.

That brings up a more important question for us then, what’s more important? Is numerical accuracy all that matters? What is a model supposed to do for us?

I think the answer is that the model we choose in general entirely depends on the problem. Up until recently we’ve never really had the option to use anything other than a pure math, glass box solution to model any given situation to the best of our ability.

It is important to state though that this does have it’s limits. The predictions of these machine learning models are based solely upon our experimental data. So if there are unusual qualities we don’t know about, we won’t be able to notice until we hit edge cases.

For example, the ultraviolet catastrophe was a fault in the Rayleigh-Jeans law that was only uncovered because we could use test the model on much smaller wavelengths that we hadn’t used in experiment to see what it would predict. Only then did we find that it was unrealistic and needed to be revised.

So how should we model reality? Do we need to understand how a particular phenomenon works in order to make meaningful use of our predictions? Or can we ignore it and go on to use machine learning to speed up research and engineering at the cost of understanding.

The Engineer in my says who cares, but the physicist in me cares quite a lot and believes that there shouldn’t be a black box in our understanding of fundamental aspects of reality like schrodinger evolution.

Sources